In the network

Critical Monthly... "We are interested in today! " Reading and writing are best done alone, yet it is common for people dedicated to literature to form communities. An example of such a loose grouping was The Critical Monthly in the 1930s and 1940s. Its mission was to keep a close eye on Czech culture. As they were scholars and poets from different parts of the country, they used written correspondence to maintain relations with each other.

Culture produces a vast number of things: books, films, exhibitions, paintings… This amount is confusing and it is difficult to distinguish what is vital, what advances knowledge and expands experiences and what, instead, does not deserve attention since it is mere repetition and uselessness. At the end of the 1930s, the periodical Kritický měsíčník (The Critical Monthly) appeared in Czechoslovakia on the initiative of the versatile literary scholar Václav Černý, who was severe in his opinions though sensitive in his search. He tried to bring stimulating ideas from abroad and ponder questions of art and society in a European context – to open the Czech milieu to the world and to let the world into it. The periodical’s contributors formed a network that was to expand and hold together in adhering to demanding ethical principles. In fact, it unravelled, tore apart and overhauled itself. Did anything remain of it?

Lukáš Prokop

The Critical Monthly

A review from 1938 to 1948 critically monitoring Czechoslovak cultural life: literature, theatre, film, fine arts, philosophy, politics and the humanities at a turning point in world history. No one needs criticism as much as a small nation in the middle of Europe! Criticism ponders what is valuable in things happening in society, what is current, what is coming into being, what is vital and can be useful. It is an adventure of the spirit to delve into things whose end is far away and whose result is uncertain! It demands all of a person, the critical individual!

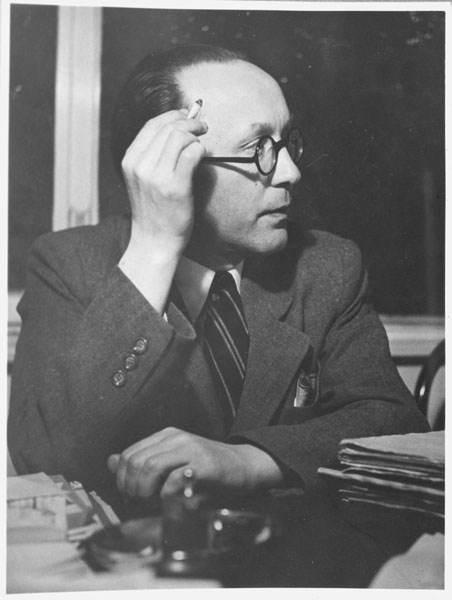

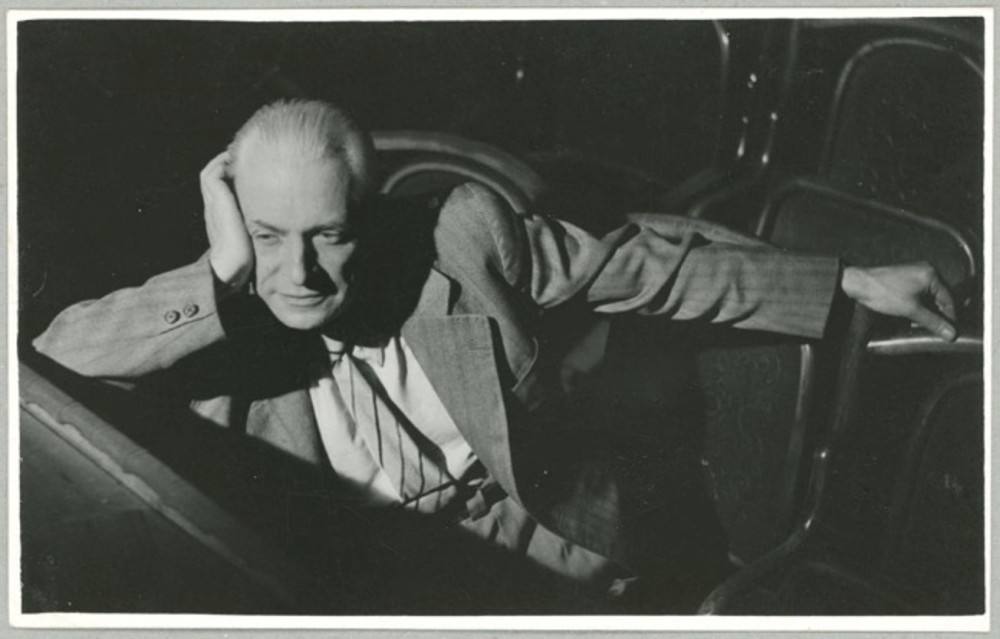

Václav Černý

1905, Jizbice u Náchoda – 1987, Prague

Literary historian, novelist, critic, translator, university teacher

One of the leading figures of Czechoslovak culture from the 1930s to the 1980s. Along with F. X. Šalda, he is probably the most important figure in Czech literary criticism. After Šalda’s death, Černý brought together a broad group of kindred-spirited poets and critics from various fields, and in 1938 published the first issue of Kritický měsíčník. On the one hand, there was the individuality and subjectivity of the contributors and, on the other, the critical community and network of poets and humanities scholars. How did they mesh? Every community is important to the extent to which it serves the growth and expansion of the individual.

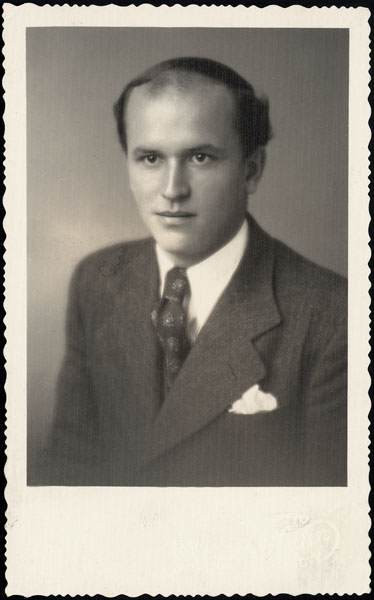

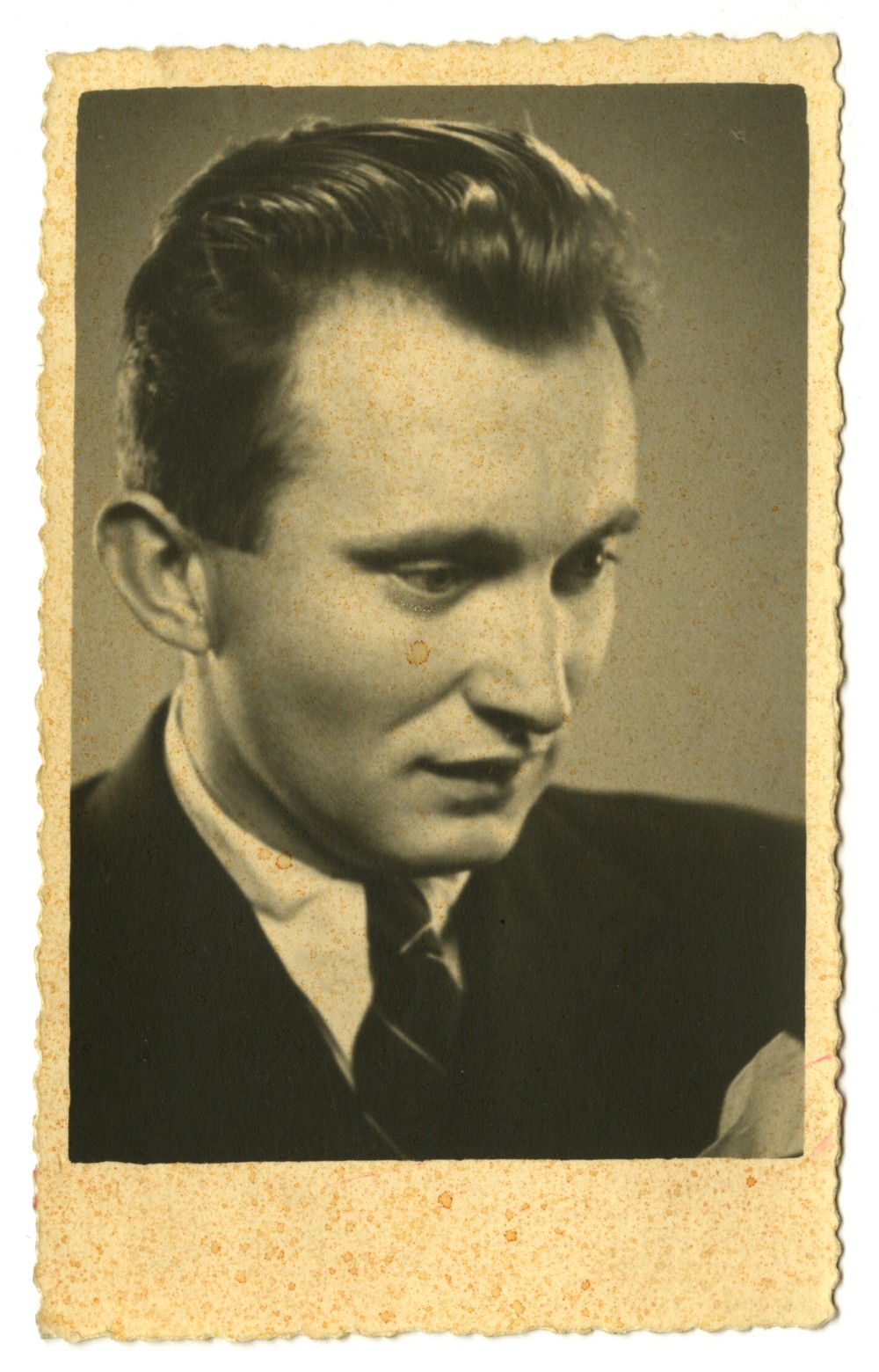

Jan Pilař

1917, Stříbřec (near Jindřichův Hradec) – 1996, Prague

Poet, translator, editor

Jan Pilař also had his place – as another of the young poets – in the pages of Kritický měsíčník. A friend of Bednář and Orten, he contributed a dose of scepticism, disappointment and doubt to the Jarní almanach básnický 1940 (The Spring Almanac of Poetry, 1940). But then once in a taxi: “I sat on the knee of the paternal Josef Hora and I was in bliss […], declaring that I was clutching the hope of Czech poetry.” With the magazine’s termination in 1948, his vision of the world partially changed. Yet the later editor-in-chief of the daily Literární noviny, then director of the Československý spisovatel (Czechoslovak Writer) publishing house, remains a tame, idyllic writer and, paradoxically, an author of love poems.

Jan Patočka

1907, Turnov – 1977, Prague

Philosopher, university teacher.

In addition to critics and young and older poets, philosophers also had their place in Kritický měsíčník. After Václav Navrátil there was Jan Patočka, who penned a superb essay on Mácha during the period of Nazi occupation. In their complexities, Patočka’s writings placed extremely high demands on readers. Although the young philosopher did not publish many of them, they represented an attempt to regard Czech society from the broadest possible perspective and always bore a severe judgment on the state of society. They had no interest in being reader-friendly. For that matter, neither did anyone at Kritický měsíčník.

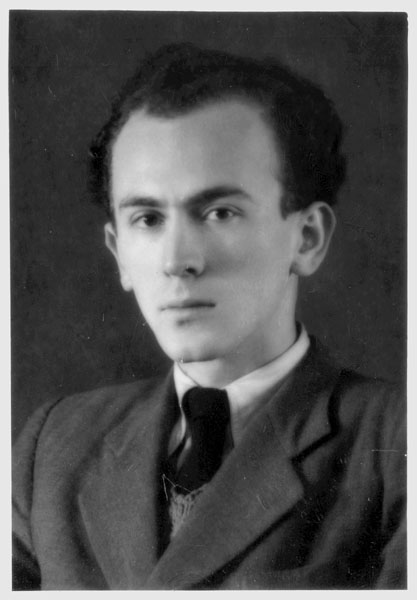

Jiří Orten

1919, Kutná Hora – 1941, Prague

Poet

If Kamil Bednář was the organizing talent of the youngest pre-war generation, then Jiří Orten was its most talented poet. An existentialist. Heightened feelings of vulnerability, fragility, a staggering longing to rediscover childhood innocence and to search for love. At first, Orten’s verse bears elements of anxiety, later there is more of an uplifting sense. There is a cosmic overreach that opens the space to romantic dreaming, and although it is heavy, its breadth lightens it. Orten was fourteen years younger than Václav Černý and nearly forty years younger than Jaromír John. All three converged in a single periodical that spoke with a modern voice.

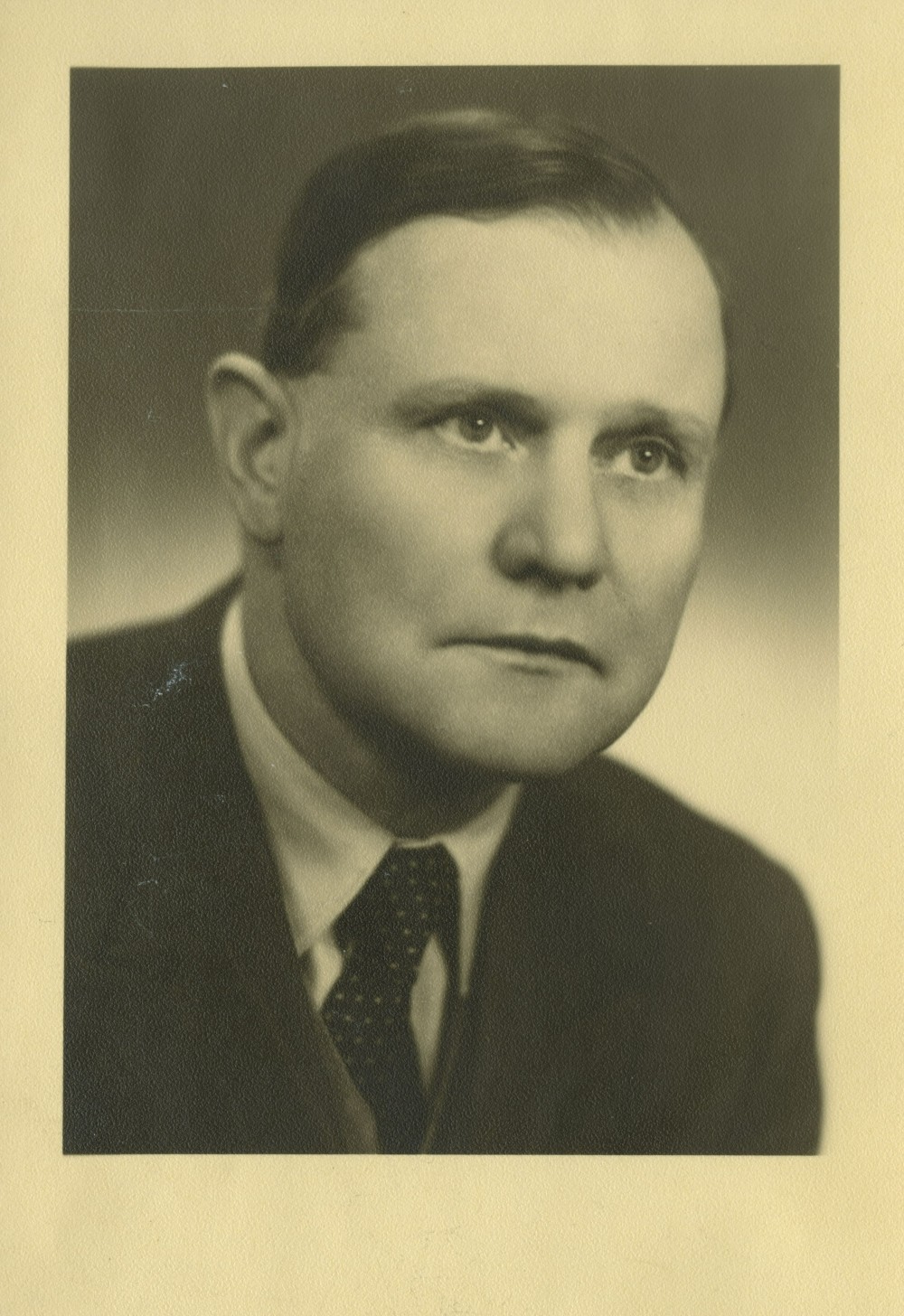

Karel Polák

1903, Kojetín – 1956, Prague

Literary critic and editor, university teacher

Traditional criticism of prose is represented in Kritický měsíčník by the writings of Karel Janů, Ota Jahoda, Antonín Hrubý, Jan Linhart, Jiří Dostál and Jiří Pistorius, as well as by Karel Polák. The latter’s contributions appear unevenly from year to year… They are characterized by objectivity, acute polemics and the attempt to explain the need for modern prose. A frequent target of Polák’s criticism is the dysfunctionality of the story, its weakness, its unlikely and sometimes meaningless course and its flimsy construction. We need originality, a new language and need not repeat old practices! The world has changed, and writing cannot be done in the old style!

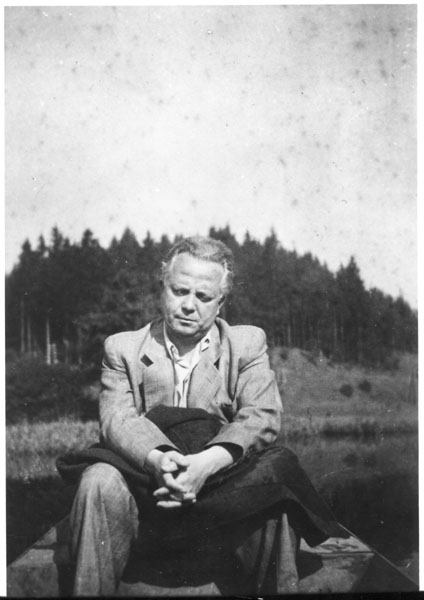

Bohumil Mathesius

1888, Prague – 1952, Prague

Translator, poet and critic

Bohumil Mathesius wrote almost exclusively essays for Kritický měsíčník, while contributing on rare occasions a news article. He was a specialist on the Soviet Union (particularly its theatre) as well as on the Qing Dynasty. The public is familiar with Mathesius as the “translator” of Zpěvů staré Číny (Songs of Ancient China). These songs had an enormous influence on generations of poets, wrote František Hrubín and Ivan Blatný. Bohumil Mathesius sought peace and harmony his entire life. As in the words of Wang Wei:

Crossing the water, I walked into the thicket

clouds upon clouds silently pass by

I am standing with village folk and chatting

Instead of going home – indeed, I lack nothing.

František Kovárna

1905, Krpy (near Mělníka) – 1952, New York (USA)

Art theoretician and critic, prose writer, essayist, university teacher

In exile from 1948, Professor František Kovárna was at Kritický měsíčník a leading and founding figure of art criticism and essay writing. He most often dealt with more general questions of art in the review. It was probably owing to the fact that the readers were more focused on literature that he wrote more extensively about art. Later, when Kritický měsíčník faced being shut down, he became the editor-in-chief of the series Svazky úvah a studií (Books of Reflections and Studies, 1939–1948). This series published a number of contributors to Kritický měsíčník.

Jan Kopecký

1919, Habrkovice (Záboří nad Labem – Habrkovice) – 1992, Prague

Theatre critic, dramaturge and director

Poetry, prose, but also theatre! Plays were to be critiqued in Kritický měsíčník by Otokar Fisher, but he had unexpectedly passed away. Thus, the year 1939 came and went without any writing on theatre in the monthly. Even after that, little space was devoted to this area of the arts. Reviews of performances? There weren’t any! Theatre had its own periodicals. It was important as a text, but performances were left to others. What next? A young student appeared, the future scholar Jan Kopecký. A writer of criticism on prose and later even of plays and theatrological essays.

František Nechvátal

1905, Velký Újezd (u Olomouce) – 1983, Tanvald

Poet, translator, editor, cultural worker

Nechvátal is today a forgotten poet and author of children’s books. He was, however, in the period of Kritický měsíčník’s publication, one of the young writers that the editors turned to. His vision of the world was important. A poet, an evangelical, a former religion teacher, a hymn composer, a writer of a barely controllable lyrical current, a singer of the great apostrophes and celebrations of life, “a savage visionary” (F. X. Šalda) and a “madman ignited by the senses” (Bohumil Polan). František Nechvátal never ceased to ask what to embrace, where to find direction, what to believe or whether to rejoice or mourn. To be of the earth or of the heavens?

Robert Konečný

1906, Brno – 1981, Brno

Literary critic, writer, poet and university teacher.

Václav Černý commuted to Brno where he became a professor of Romance studies at Masaryk University. The poet Ivan Blatný also lived in Brno, as did the critic and later professor and writer Robert Konečný. The latter spent six long years in prison in Brno and in Wroclaw, Poland; his Písně z cely (Songs from Jail) went practically unnoticed by readers. In his essays, which he also published in Kritický měsíčník, Konečný did not shy away from his interest in psychiatry; the medically diagnostic tone of these articles contribute to the uniqueness of the periodical’s diverse views.

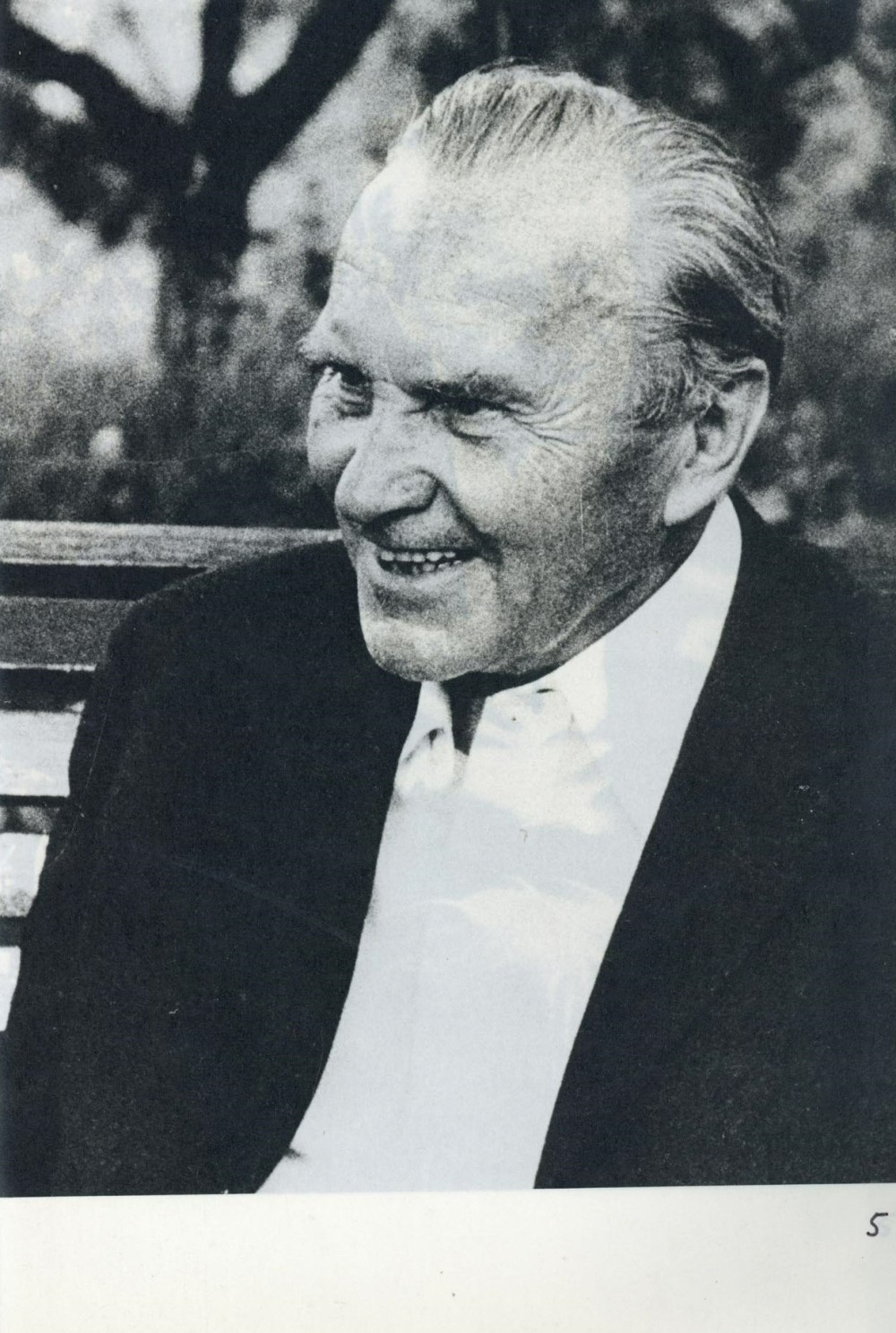

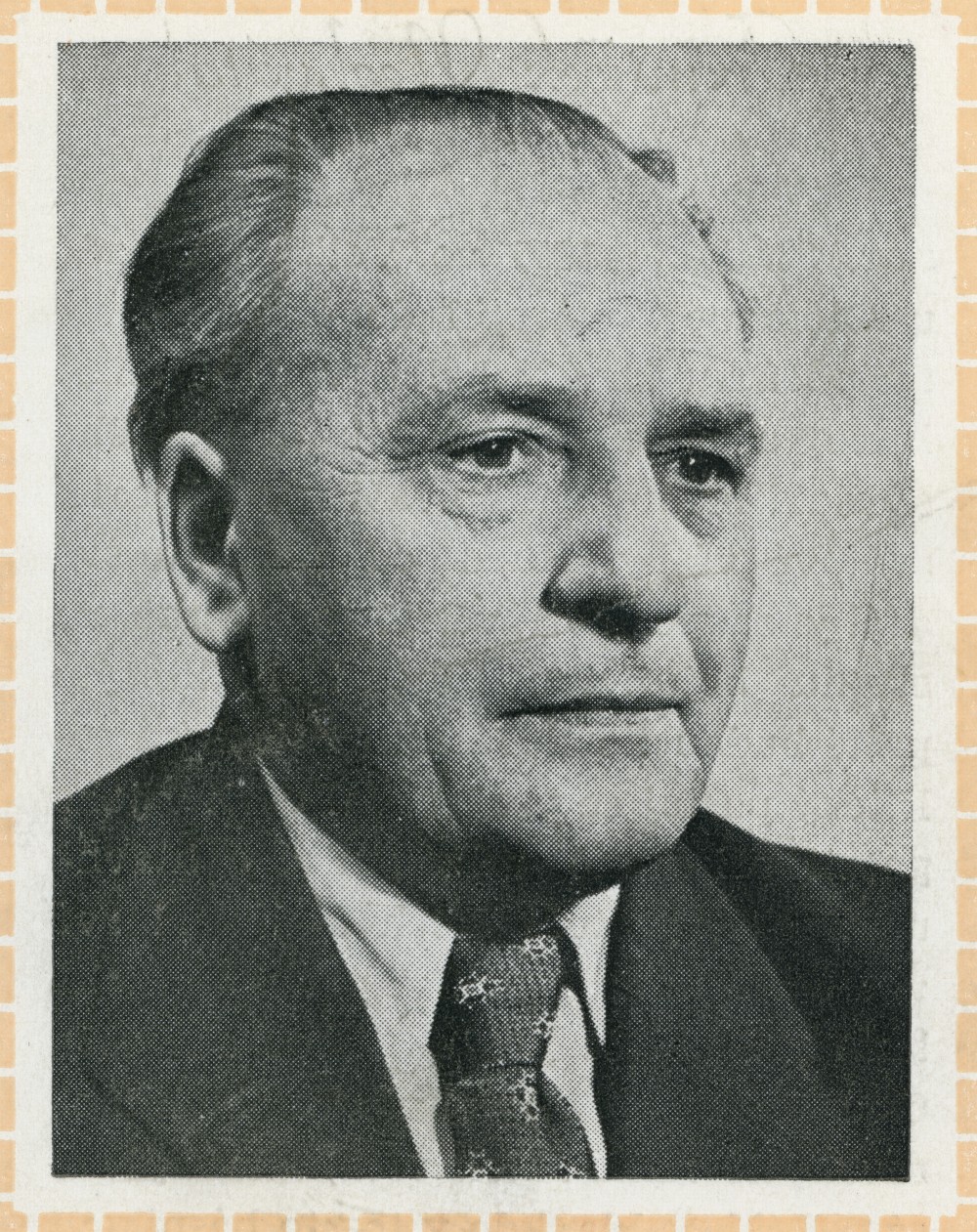

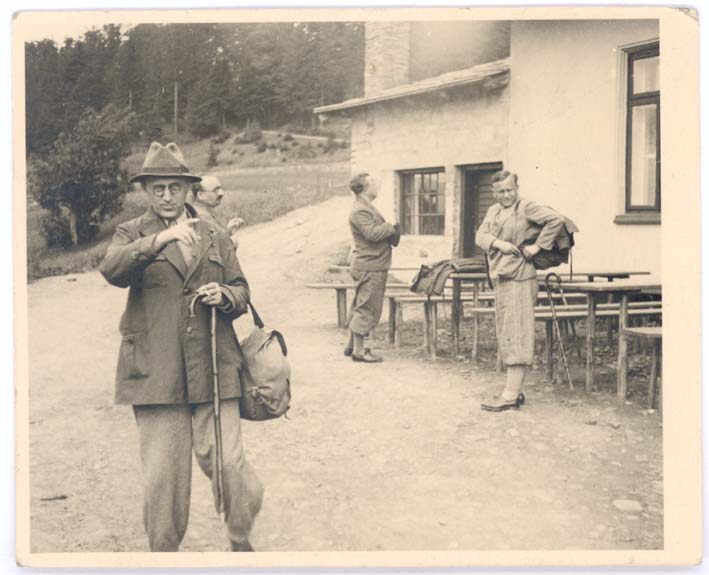

Jaromír John

1882, Klatovy – 1952, Jaroměř

Prose writer, editor, aesthetician, university teacher

John was among those who formed the core of Kritický měsíčník. He lived inside a man named Bohumil Markalous and came to life when Markalous, who went on to become professor of aesthetics, was not working or went to sleep. The rule applied that if Markalous progressed, John too had to advance. It was not until the Nazi occupation, when they moved together to the town of Nové město nad Metují and later to Slatiňany, that John felt in his element. He could finally write to his heart’s content! But then Markalous once again assumed an office, even though John knew of it and warned against it.

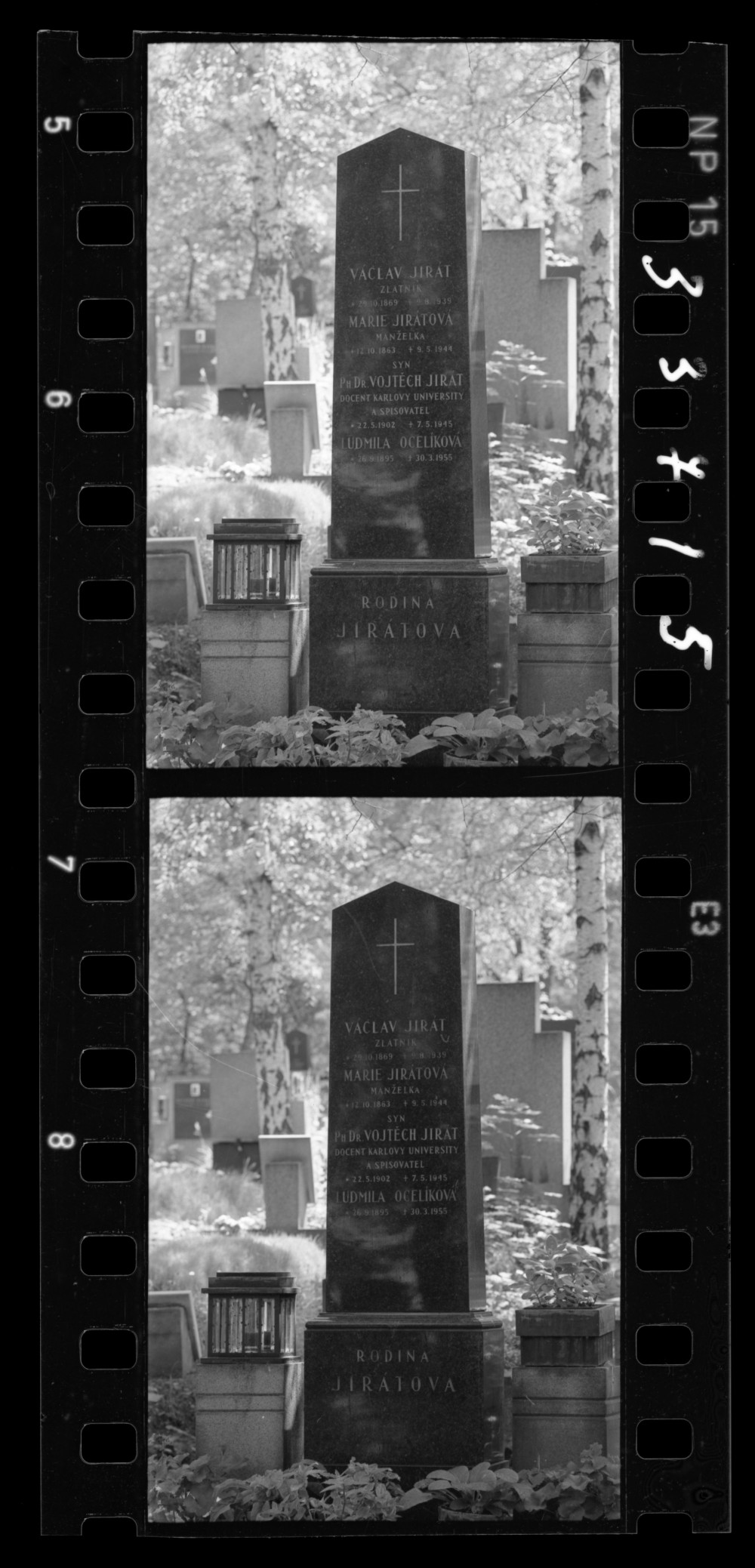

Vojtěch Jirát

1902, Praha – 1945, Prague

Literary historian, Germanist, critic, editor, essayist, university teacher

Vojtěch Jirát, a student of the Romantic scholar Otokar Fischer, longed to “combine literary research with art”. A scholar must be creative! Jirát was a Germanist by profession, but with the war approaching he became increasingly focused on Bohemian studies: “I too must provide strength,” he confided. For Kritický měsíčník he mainly wrote essays on the National Revival period. As with others, it was about criticism, about an accessible and accurate evaluation. Jirát was devoted to the Muse and strove to see old things with young eyes. He died at the end of the war.

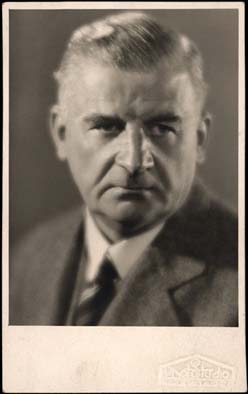

Josef Hora

1891, Dobříň (u Roudnice nad Labem) – 1945, Prague

Poet, editor, translator, journalist

In 1938, when the first issue of Kritický měsíčník was published, Josef Hora had already written his best collections of poems: Tvůj hlas (Your Voice), Tonoucí stíny (Fading Shadows) and Máchovské variace (Variations on Mácha). Readers and critics justifiably perceived him as a proletarian poet who deserted the cause to explore time. The poet began this difficult and dangerous research as an editor for the dailies Rudé práva and for the social-democrat leaning České slovo, in his garden in Dobřín, and continued in it in Florence. He observed it at the train station: trains and tracks, wave after wave, travelling, on the beach, among the pines near the Elbe, around the river, behind a table, in a “dream-like train”, through the window “in the liquid darkness”.

Vladimír Holan

1905, Prague – 1980, Prague

Poet, editor, translator

If Josef Hora is considered the poet of passing time and of merging in the waves of a river flowing into “other worlds”, Holan is in the minds of critics of Kritický měsíčník the poet of solitude, depth, darkness and the setting sun. Where one sets in motion, the other prefers to stop, and either rise or fall: “Solitude is for me a prerequisite for work. Yet my isolation never meant an isolation from life or human destiny; it was the isolation needed for work.”

František Halas

1901, Brno – 1949, Prague

Poet, editor, translator, librarian

František Halas was also one of the founding figures of modern Czech poetry. His presence at Kritický měsíčník, along with Hora, Holan and Orten, attests to Černý’s attempt to concentrate the best poetry of the day in a single place. Halas also possessed an extensive overview. He wanted to be close to the Czech poetry of the younger generation. What was Halas the poet like? What was his subject? Death. And how death, referring to nothingness, the fall and the end, gives zeal to life: not to die by death, but, through a heightened existence, “to die by life!”

Pavel Eisner

1889, Prague – 1958, Prague

Translator, editor, essayist and writer

Pavel Eisner was not a writer at the Czech Chamber of Commerce, but only after he had left the office and returned home. It was then, and even more intensely during the Nazi occupation, that he claimed his life multiplied. This is because the Czech language requires “a hot and passionate lover”, he exclaims a few years later in the pages of Sonety kněžně (Sonnets to a Princess). “There was practically no literary or otherwise artistically active person that Pavel Eisner would not have known,” said his wife. Eisner is the author of monumental books on the Czech language that are written in an uplifting, even lovingly exalted style. Are they still vital today?

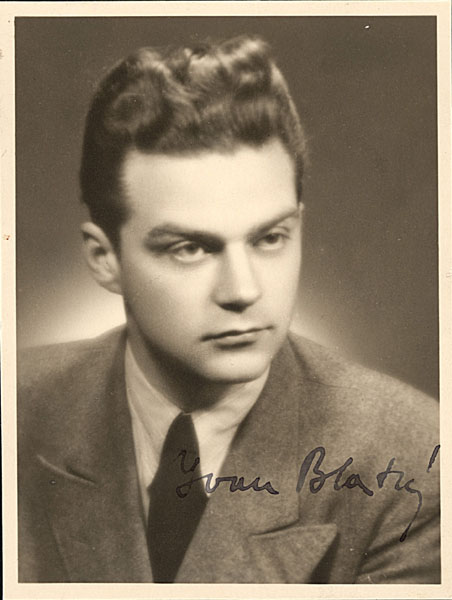

Ivan Blatný

1919, Brno – 1990, Colchester (UK)

Poet

The world of Blatný’s Melancholické procházky (Melancholic Walks) is not only the mood of Brno and sombre still lifes; it also consists of existential feelings of loneliness and emptiness. The courage to seek a new poetics is evident in his verse. The four collections of poems that Blatný wrote before emigrating in 1948 capture distinct changes in his poetics from the melodic poems of his first collection to the “civilist” poetics drawing from the aesthetic principles of the Skupina 42 group. “I say that every moment is worthy of a poem / I attempt it on the street where there is a heavy frost! / In a hardened worn-down mind from which no music emanates / In a nest where there is no hatchery of metaphors”.

Kamil Bednář

1912, Prague – 1972, Mělník

Poet, translator, editor

Bednář’s poetry responded to the call by Kritický měsíčník for that which was current, nascent and hesitant, imprecise and nebulous. It is in this spirit that the manifesto Slovo k mladým (A Word to the Young), in which the author intended to speak for his generation, was written. “Kamil was the acknowledged leader, the oldest of us. […] he had an inclination for meditation, which is why his collections and books of poetry, whose number by the end of his live rivalled Vrchlický’s, had a rather abstract character.” (Jan Pilař). Bednář’s poetry grows in many directions: lovingly dreamy, longing and bittersweet such as Milenka modř (My Lover Blue, 1939), subsiding such as Po všech svatbách světa (After All the Weddings of the World), festive and defiant, apocalyptic and sceptical, though losing its persuasiveness with each and every collection.

Bohumil Polan

1887, Plzeň – 1971, Plzeň

Literary and theatre critic, poet, essayist, librarian

The westernmost contributor to Kritický měsíčník was verifiably the librarian Bohumil Polan, who wrote under the name Čuřín. In his criticism, he is a student of Šalda, renouncing only the latter’s polemicizing tendencies and affected expressiveness. His numerous writings in Kritický měsíčník are precise, concise, focused and yet: we should let ourselves be carried away: go with the writer wherever his heart takes him! Polan’s language may sound stumbling, even archaic at times. Polan was one of the oldest writers for Kritický měsíčník. He carefully and knowledgeably kept abreast with prose and poetry, even that of the youngest generation.